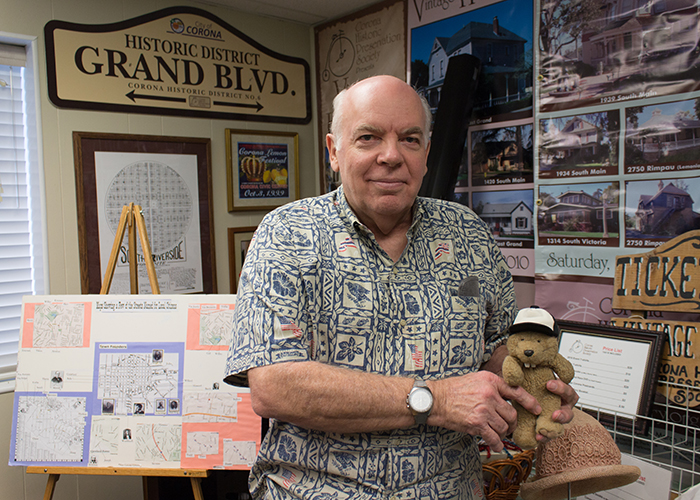

I met Richard Winn on a warm spring day in the corridor outside Corona’s Historic Civic Center. I had loads of questions. As co-chair of the historical marker committee at the Corona Historic Preservation Society, he was responsible for replacing the Old Temescal Road historical landmark, which had been stolen. I wanted to learn more about him and his way of commemorating history.

Before |

After |

“My family are pioneers that came to the west in 1848 and 1850,” he said after we’d stepped into the Society’s tiny shared meeting room. “They lived through the Indian fights and all those kind of things that occurred. They were largely agricultural based. I still love the idea of hooking up a plow to a horse and plowing.”

Richard and his wife, Mary, moved to Corona in 1976. Neither of them were historians, or agriculturalists for that matter. Richard was a safety engineer and Air Force veteran, Mary a dental hygienist. A fateful call from one of Mary’s friends brought them into the realm of historic preservation in 1983, and they became some of the original charter members of the Corona Historic Preservation Society.

Since then, Richard has helped place twenty-two historical markers around the city of Corona, named for its famous Grand Boulevard, which encircles the entire heart of the city and was a course for world-class road races in the mid 1910s. These markers commemorate important sites on the city, state, and national levels. Some are bronze, but most are granite, polished to a fine sheen with either an engraved image of the site in its original condition, or a QR code linking visitors to the Society’s website.

“It’s more affordable, more permanent as well,” Richard assured me as he broke out a massive stack of printed landmark profiles, “and thirdly, polished granite shows up more than bronze. And, you don’t have to worry about people stealing it. We’ve had people steal all kinds of things. In fact, we have a couple of historic markers that we would prefer somebody would steal. Then we could correct them.”

Though not a historian by trade, Richard cites his background in safety and construction as the main reasons he got the state’s attention regarding local landmarks. It was his eye for detail that got his proposal to add the Jefferson Elementary School to the National Register taken seriously. This school, which didn’t have enough space or letters to spell out Thomas Jefferson Elementary School, nonetheless had fifteen exquisitely carved escutcheons on its façade, portraying science, engineering, and art. When Richard wrote about those escutcheons, which are no longer carved on schools, the State Office of Historic Preservation was highly impressed.

What makes the Society’s approach especially unique is their involvement with local Boy Scout troops. For their Eagle Scout projects, scouts can sign on to conceive, fundraise, and install a new historical marker, with adult supervision, of course. This helps defray expenses for the Society, which already has a small enough budget, and builds valuable life skills for the scouts. Fifteen of Corona’s twenty-two markers have been installed with the help of individual Eagle Scouts!

“Most Boy Scouts that I have dealt with in this unit—I was a scoutmaster for five years myself,” beamed Richard, “will never, ever become plumbers or work for the gas company where they have to dig ditches.”

Then he flipped through the marker profile printouts, one by one: The elegant Carnegie Library, which served the community from 1906 until 1971, was bulldozed overnight by a shady city manager to make room for a chicken franchise that was never built. Today, the site is still a dirt lot, but there is at least a polished, black marker with a photo of the library to remind folks of how the beautiful building once looked.

He pointed out that the start/finish line of the road races has been commemorated with a plaque, as well as the 1904 Hotel del Rey, which has been dismantled, piece by piece, and stored away in C containers until the place and funding are right to rebuild it somewhere else.

“Now our goal is to get younger people involved so they can take over, because of our first hundred members, I don’t think twenty are still alive. Even fewer of those are still local.”

Richard admits that he and his wife would love to see leadership of the Society pass on to someone in the next generation. The Society has plenty of room to grow and even hire paid experts, which would make them eligible for grants. It turns out historical grant writers tend to snub historical societies that don’t have property or a payroll. Meanwhile, the Corona Historic Preservation Society continues to hold big dedication ceremonies and give historic house tours to garner public interest.

My interest was certainly piqued. After learning about liquid nails, plaster, and the deep pits that anchor plaque bases in place, I am ready to start restoring history. The use of granite is a great idea, and I believe that many landmarks on the state level, especially the Twentieth Century Folk Art Environments, will benefit from having images of their original appearance engraved on them.

“[Corona] has a great heritage: citrus, railroad—I mean we’re one of the few cities founded in the 80’s during the boom, that was along a rail line that survived. Here and Upland. That’s about it. So we think it’s worthwhile preserving this stuff.”

To help the helpers at the Corona Historic Preservation Society, visit their website Corona-History.org.