Previous Day |

Anniston, AL → Birmingham, AL → Montgomery, AL 244.0 mi (392.7 km) |

Next Day |

There’s a storm comin’, everyone!

Specifically, it’s a Saskatchewan Screamer, and it is heading down from Canada to pummel the Southeast! I actually rewrote my route today because of it, so I’ll be narrowly dodging the thunderstorms and hopefully the strongest of the blizzards! But first, breakfast! The Hotel Finial had a lovely spread, and with a hearty stack of Liège waffles and a cafécito, I was off to follow the path of the Freedom Riders!

|

|

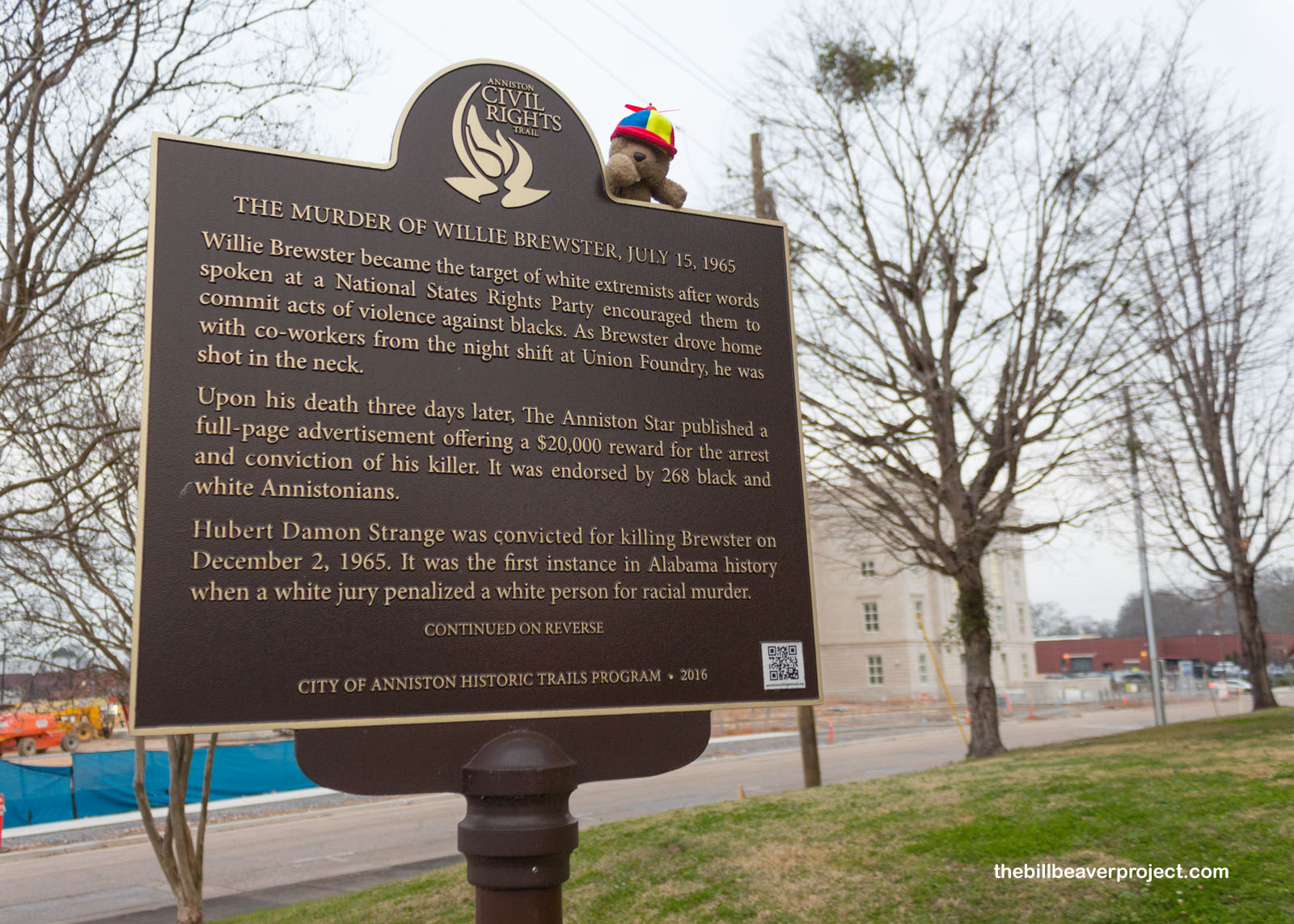

The world that spawned the Freedom Riders was pretty grim. Right next to the county courthouse, a plaque marked the site of the murder of Willie Brewster on July 15, 1965. He was shot in the neck by white extremists on his way home from work, and while his case was the first in Alabama when a white jury convicted a white person for killing a Black person, Mr. Brewster’s story was not uncommon in the South.

|

In fact, Mr. Brewster was murdered four years after the Freedom Riders got on the bus in 1961. Who were these brave folks? I was about to find out by visiting the pretty new (2017) Freedom Riders National Monument, a short ride from the hotel.

|

See, in 1960s Alabama, there were very strict rules about riding buses. More specifically, if you were Black, you had to sit at the back, because white folks at the time thought being Black was somehow bad. A set of laws, known as Jim Crow laws, had been legitimized in 1896 by the Supreme Court case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, which applied “separate but equal” to all sorts of public spaces like restaurants, restrooms, and, of course, public transportation. The term, “Jim Crow” probably originated with the 1830 minstrel shows of Thomas “Daddy” Rice, who performed in what we now call blackface and capitalized on Black stereotypes.

|

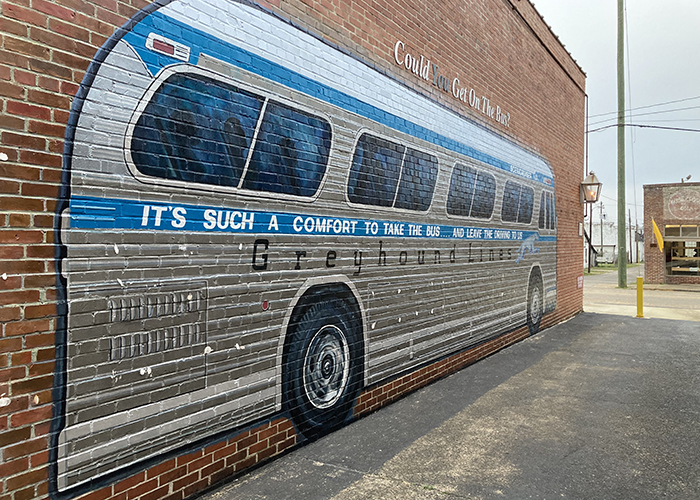

Well, as you can imagine, by the ’60s, a lot of folks had just about had it with this nonsense. In 1961, thirteen folks of multiple races, called the Congress of Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.) set out to poke holes in these laws. The year prior, the Supreme Court had ruled in Boynton v. Virginia that segregation in public transportation across state lines violated the Interstate Commerce Act, so it made sense that interstate buses would be the place to put these policies to the test! It did not go smoothly! White segregationists attacked an integrated Greyhound bus, en route from Atlanta to Birmingham, breaking windows and slashing tires!

|

|

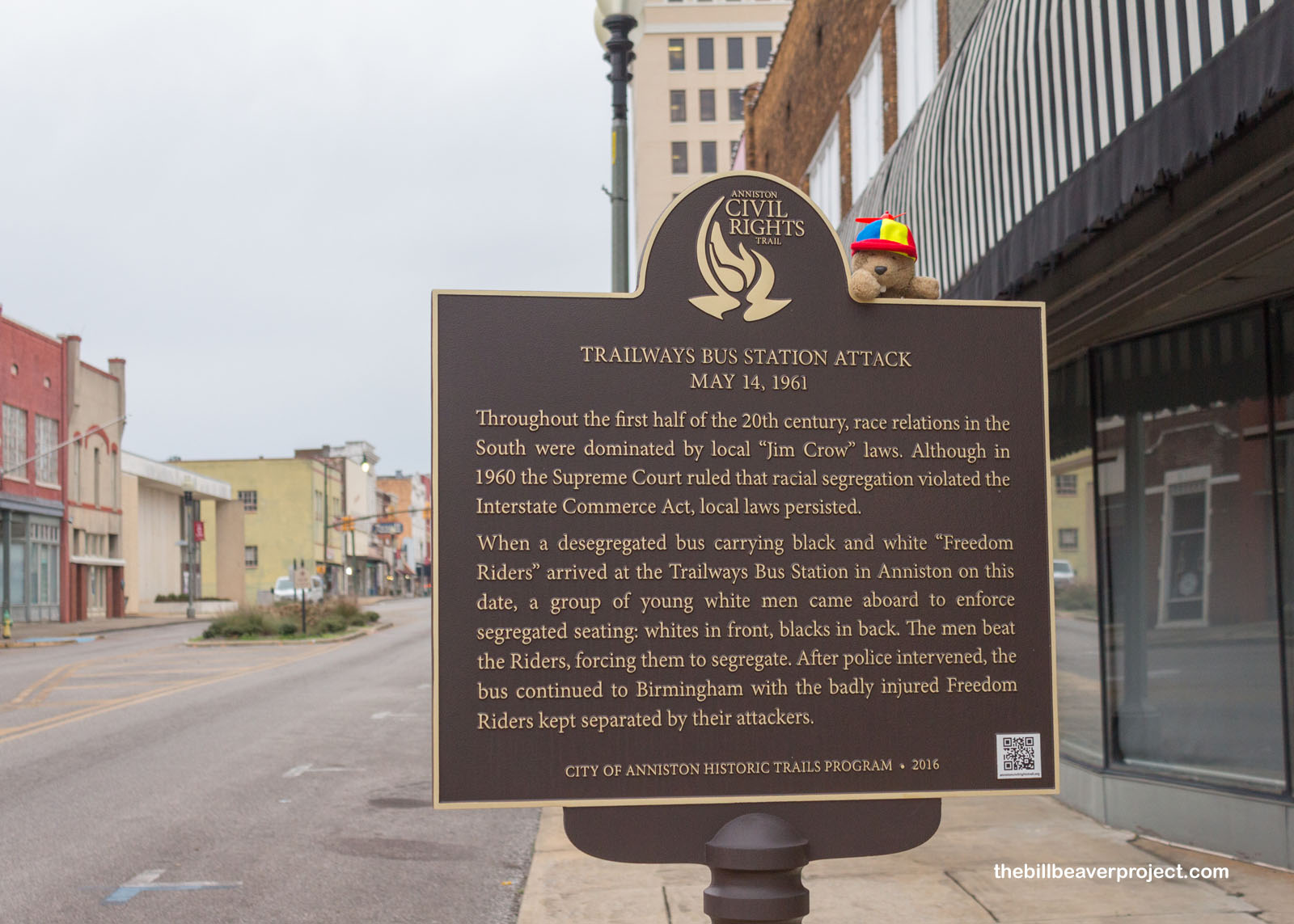

Something similar happened not far away at the Trailways Bus Station, but on this bus, the segregationists boarded and beat the passengers who were standing up against discrimination! This bus was able to continue the journey to Birmingham, but the segregationists stayed on board, forcing the Black folks to stay separate from white folks the whole way!

|

|

About six miles west of Anniston, there is a plaque at the site where that first Greyhound bus stopped to change the tires that were slashed back in town. The mob of segregationists followed the bus here and set it on fire, attacking the passengers as they got off the bus! It turned out, attacking a bunch of unarmed folks didn’t look too good for them! The number of Freedom Riders swelled from 13 to 400, and by November 1, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) had new regulations banning segregation on buses and terminals for interstate bus lines! It was not the end of segregation, but it sure was a big hit!

|

After paying respects to the Freedom Riders, I dipped south and a little off topic, but in the direction of another national park unit called Horseshoe Bend National Military Park. Unlike most of the battlefields I’d be touring on this adventure, the battle at Horseshoe Bend took place way back in 1814!

|

While the new USA was in its second war with Britain, the Muskogee, or Creek, Nation was in a civil war of its own! At stake was land sovereignty! See, they’d been promised autonomy over their traditional lands (most of modern Alabama and Georgia) by the Treaty of New York in 1790, but after the Revolution, Americans were itching for more land, mostly for plantations. In 1810, there were 9,000 non-Native residents in Creek Territory, 128,000 by 1820! Handling this complex situation came down to the Creek National Council, who cooperated with the US Government, versus the Red Sticks under Chief Menawa, who believed in resisting the land grab at all costs!

|

War broke out in 1813 between the National Council and the Red Sticks after the Council executed two Creek warriors at the request of the US government. Already at war with Britain, the US worried that their British opponents might turn this conflict to their advantage, and began their own campaign against the Red Sticks, first at Littafuchee in 1813, then pushing further south until they reached the Tallapoosa River. Here, in the river’s horseshoe bend, many refugees had gathered in Tohopeka, a fortified village, which was protected on one side by a large wall!

|

|

Andrew Jackson and the Tennessee Militia attacked this wall in March of 1814. Today, this wall, defended by 1,000 Red Stick warriors, is marked out by white stakes, but at the time, it was completely impenetrable! After two hours of bombarding it, the Tennessee Militia needed to come up with a new strategy.

|

Atop a nearby hill, a stone marker memorializes their victory in battle, but the cannon is misleading! The Tennessee militia didn’t win the Battle of Horseshoe Bend by shooting down the wall. They won by sneaking around!

|

The US Military had made alliances with the Cherokee and Lower Creek, whom they would later betray anyway, and these warriors, with deer tails in their hair to distinguish them, crossed the Tallapoosa River while the Red Sticks were distracted by the cannons. Stealing canoes, they brought all their forces across to attack Tohopeka. The battle overwhelmed the Red Sticks, who ultimately had to forfeit the war and 23 million acres of land with the Treaty of Fort Jackson. The Creek War had destroyed 48 Muskogee towns, leaving many destitute, and the new state of Alabama subjected them to “like it or leave” laws. Then, in 1830, the Indian Removal Act forced the last of the Creek to leave for Oklahoma. They carried 44 ceremonial fires, always to be kept burning, and today, 16 still are!

|

|

Having rounded the Bend, I used some momentum to slingshot my way to the city of Birmingham, a city founded upon industry! It’s a pretty young city, all things considered, built in 1871 during Reconstruction and named for Birmingham, England! It made a name for itself in iron, mining, and railroading!

|

The industries of Birmingham are memorialized here at Vulcan Park, where the world’s largest cast-iron statue looks out over the city! Designed by Italian artist, Giuseppe Moretti, in 1904, the Roman Smith God has looked out from this spot on Red Mountain since the 1930s!

|

There’s plenty to explore of Birmingham’s iron industry, especially the Nationally Registered Sloss Furnaces, founded in 1880 by Colonel James Withers Sloss! Today, though it’s been renovated and its oldest building only goes back to 1902, the Sloss Furnaces are America’s only 20th-century blast furnace being preserved and interpreted as an historic industrial site!

|

Though the rain from the building storm had already gotten started, I got out my flutter phone to take a look around! What you’re seeing here is the Number 1 Furnace and Cast Shed, where ore would be melted down at 3,800°F into molten iron and a waste product called slag! They would then pour the molten iron into casts dug into the sandy floor and remove the bars after they had cooled!

The iron produced here at Sloss was called pig iron, because when they poured it out into bars, the workers thought they resembled piglets around a sow! This is sort of a crude iron that’s been extracted from the ore and shaped into bars for shipping and more processing!

|

|

These furnaces were a big deal! Over 24,000 tons of iron came out of the Sloss Furnaces in 1882, the year it went live! That amount grew and grew through the sale and reorganizing of the furnaces in 1899, and by World War I, the new Sloss-Sheffield Furnaces were among the largest pig iron producers in the world!

|

|

And yet, like with most places I would be visiting on this adventure, the Sloss Furnaces had their fair share of racism. Most of the labor force was Black, segregated by strict hierarchy to use different time cards and bathhouses, and even to attend different company events! With this separateness came conflict, even violence, like the murder of Tom Redmond on June 17, 1890! This continued through 1928 when Sloss-Sheffield began leasing convicts, still mostly Black, to work the furnaces, and into the 1960s when the Jim Crow laws finally went belly-up.

|

A lot of the work that went into making that happen came from this man, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. who came to this very Birmingham jail on April 16, 1965. He’d been arrested for leading a protest against segregation after protests against segregation had been banned, and here, he penned a 7,000-word letter to local religious leaders who had been asking him to take a seat and be patient. Dr. King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail reminded them that “Justice too long delayed is justice denied,” and that moderates needed to stop nay-saying and start lending more support to their movement so justice and equality could finally be achieved. It remains one of the most important documents to come out of the civil rights era, and I really think you should read it.

|

By this time, the rain was picking up, the wind was blowing, and snow was in the forecast, so I headed south to Montgomery, checking into the Hampton Inn & Suites Montgomery-Downtown, and cranked up the heater to recharge for the next day of adventure. It was only then that I realized, after going through the places I’d visited, I’d miscategorized Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument on my map and skipped it! Oh no! I will have to figure out a way to get back to Birmingham on a future adventure.

|

For now, I’m not going anywhere, because it is dark, cold, and snowy outside. I’ll rest up, and tomorrow, I will rejoin the footsteps of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in his famous march from Selma to Montgomery!

Like Snow White, I’m snoozing!

Previous Day |

Total Ground Covered: 556.0 mi (894.8 km) |

Next Day |