Previous Day |

Grants, NM → Zuni, NM 75.2 mi (121.0 km) |

A Bit Later |

Good morro, everyone!

As you might have guessed from the title, I got up bright and early and cold because I had a ton of ideas for things to see today, starting with my next New Mexican national park unit, El Morro National Monument! Named for a historic morro, or bluff, this spot has been a place to rest and record for thousands of years!

|

|

After checking in at the visitor center, I started my wander around this small park on the Inscription Loop Trail, because that was going to pass the great morro with its many petroglyphs and historic signatures dating back to Ancestral Puebloan times.

|

Behold! This east-facing cliff is impressive on its own, visible for miles in all directions! In ancient times, the base of the ground was as high as the top of the bluff, but as eons passed, the softer parts have eroded away, leaving behind this spectacular cuesta, a wave-shaped landform, that I was about to view up close and personal!

|

What attracted so many folks here over the centuries was this pool, which gathered runoff and rainwater (lidokkya in Zuni) to rehydrate thirsty travelers passing through the area. It was first written about on March 11, 1583 by Antonio de Espejo while he was searching for two Franciscan friars, who had gone missing two years earlier. He called this pool El Estanque de Peñol, or “the pool at the great rock!” Today, no humans are drinking from this pool, but it is home to some unique tiger salamanders (dew’a:shi in Zuni) that never fully leave their larval stage! These are called neotonic salamanders! Being winter, there were no active salamanders to greet, so I moved on to the first inscription!

|

Each piece of the etching puzzle at El Morro was added in its own time over the centuries. It just so happened that the first I photographed was one of the oldest, a collection of hand-shaped petroglyphs dating back to time immemorial! In fact, there are over 2,000 petroglyphs on this cliff! Without metal tools, ancient folks used antlers or hard hammerstones to leave these enduring marks on A’ts’ina, which is the modern Zuni name for this “marked rock!”

|

In non-chronological order, the next inscription of note dated back to 1857 and belonged to “Peachy” Breckenridge, the man in charge of 25 camels under Lieutenant Edward Beale! Yes, folks, the famed Camel Corps passed this way to open up a wagon route between Fort Smith, Arkansas and the Colorado River. Following the ancient, treacherous, 73-mile Zuni-Acoma trail, Beale’s trail became a major route to get into Arizona, but water was so scarce, it didn’t get used much past the river.

|

The third culture represented at El Morro was mostly in variations of the Spanish phrase “pasó por aquí,” or “passed by here.” The first of those that I saw was left behind by Ramón García Jurado who pasó por aquí on June 25, 1709. Based on the date, he was likely on his way to attack the Diné (Navajo) under orders of (deep breath) Governor Admiral Don Joseph Chacón Medina Salazar y Villaseñor, Marques de la Peñuela, whose name would not be appearing on this rock!

|

But at least one Spanish leader left a message on A’ts’ina, and that leader was Don Juan de Oñate, who pasó por aquí on April 16, 1605 while returning from a quest to find the “South Sea,” known today as the Gulf of California! Apart from this mission, Don Oñate’s quests were mostly met with disappointment. There were no fabled riches or really any precious metals to be found in New Mexico, so this area would remain a colony of agricultural villages for a long time!

|

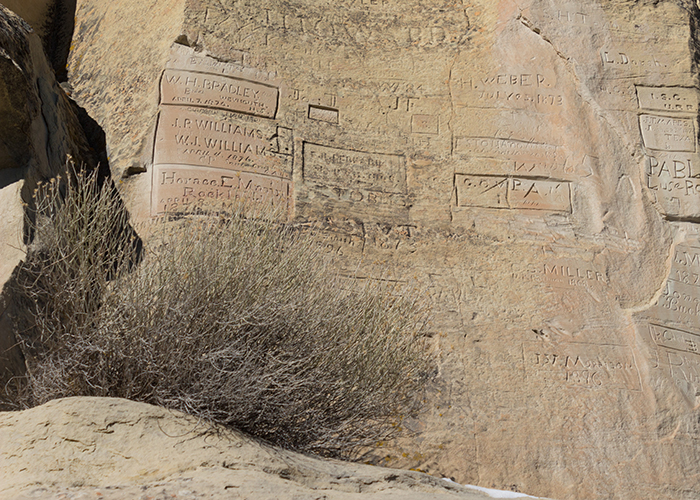

At Stop 11, I got out my Flutter Phone to give a more comprehensive look at how dense these inscriptions were! As you can see, there are tons of Native, Spanish, and English writings clustered together in a single space behind me!

Ultimately, I had to reach the end of Inscription Rock, which also marked the end of El Morro’s time as a stopping point. Here, a survey crew for the Union Pacific Railroad stopped and carved their names in rectangular blocks in 1868, some of the last inscriptions (legally, at least). Ultimately, the railroad swerved north by about twenty-five miles, becoming the main east-west transportation route, followed by I-40 in the 1950s. That meant folks didn’t have much reason to stop by El Morro for water anymore!

|

|

Speaking of rerouting, I couldn’t complete the full loop of the Headlands Trail today, because the blizzard a few days back had left one whole side of the cuesta covered in treacherous, icy conditions! Nonetheless, I was not about to be deterred from finding another way to the tippy-top!

|

As I headed back toward the split in the trail, I found a surprising sign! Charles Fletcher Lummis pasó por aquí in 1892, three years before he built the historical landmark that launched my grand adventure! Though he did not write his name on Inscription Rock, he did write about El Morro as “…the most precious cliff, historically, possessed by any nation on earth!”

|

I followed the loop back to the fork and headed the other direction. Wouldn’t you know it, but I was actually starting to feel pretty warm, even though it was just above 20°F! I wondered if there would be enough snow up here for Señor Castorieti to make a long-deferred appearance. After all, I haven’t seen the snow beaver since 2020! But, no matter how much I patted it, the snow up here was much too dry and powdery. I would not be seeing my mysterious friend today.

|

|

Instead, I faced stairs, lots of stairs! A’ts’ina is a tall rock, and there was only so much space for switchbacks, but it would all (huff) be worth it (puff) to see the ancient village awaiting me at the summit!

|

And here it was, Heshoda A’ts’ina, the pueblo on the inscribed rock! It was most likely occupied somewhere between 1275 and 1400 AD, the height of the Ancestral Puebloan period, and while 18 rooms were excavated here in the 1950s and ’60s, scans have revealed that this was a whole town of over 800 rooms! The folks who lived here collected water in cisterns on top of the rock and grew their crops on the plains below! It’s unknown why they left after 75 years, maybe drought, but they would later assemble in larger pueblos like the one I wanted to visit next.

|

|

The Pueblo of Zuni was founded in 1699, but its roots here stretch back much further. The original pueblos here comprised the seven fabled cities of Cibola that Vásquez de Coronado sought unsuccessfully in 1540, and the ruins of those towns still exist for touring! I had the notion that I could book a tour of these ancient pueblos, but not only was the visitor center only open on weekdays, but the entire pueblo only allowed photography with a permit from the visitor center. In short, I would be taking pizza, not pictures, in the historic pueblo of Zuni today. Let that be a lesson to explorers of New Mexico: when visiting pueblos, triple check the special rules for visitors, because these communities have endured a lot of outside stress over the generations!

|

So instead, I had to reimagine everything I planned to do for the day. I’d meant to hold off on visiting my next national park site, El Malpais National Monument, until tomorrow, but with a sudden glut of time, I had a whole afternoon to hike up the El Calderón trail! Doing so, I took enough photos there to fill a whole other blog, so stay tuned for Part 2!

Hasta la cuesta!

Previous Day |

Total Ground Covered: 159.9 mi (257.3 km) |

A Bit Later |